If you haven’t read the first guest post written by Fiona, you definitely should – click here. It’s always been my idea to have this blog as a space that would help me reflect on teaching, learning, and education in general. I’m really thankful to Fiona, as she’s certainly helped me do some thinking, and I’m sure this will be the same reaction that many of you will have. My opinion may even be biased, as her words strike a chord with my views, but even if that’s not the case, there’s good food for thought below. 😉

Postman knocked twice

Remember the film? Originally The Postman Always Rings Twice, but a sliver of poetic licence is not a crime, and has a double purpose here. First of all, there’s the dogme connection: one has to admit That Scene is an admirable example of making good use of what’s in the room.

But more to the point, Postman. At the recent ISTEK conference, Scott Thornbury named New Yorker Neil Postman as another of the major influences on his career and professional ‘take’ on ELT. (see Holes-in-the-Wall for more on when and where). Scott showed his audience a video of Postman ostensibly poo-pooing the use of technology, and great hoo-ha ensued, with Twitter alight seconds after the Postman segment of the talk. Tweets slyly winked at Scott for praising Sugata Mitra for his experiment using computers AND a man whose entire ethos was against technology. ‘Hmm’ I thought. Again, either it was me, or the reactions were too quick, the pouncing too keen, and there was obviously more to all this….surely?

Then, not long after, came the second knocking when another wave of attacks surged forth on blogs, facebook and elsewhere. So who was this Postman chap capable of provoking the audible clashing of virtual swords? Could his ideas really be that off-target AND influence someone who, let’s face it, is pretty major in our field?

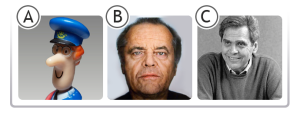

In this post, I'm talking about one of the above; is it a), b) or c)? / Photos by a) José Camba b) cliff1066 c) unknown Many thanks to Brad Patterson as montage-meister.

Neil Postman was an American media theorist – one of the pioneers in the field – author and educator well-known for his attacks on the role of television and technology in (US) society. As a humanist, he was concerned that modern life was about machines rather than people, information rather than ideas, and he felt that television was taking over from school as the main source of information. He wrote around 18 books including Amusing ourselves to death and Teaching as a Subversive Activity, and he was particularly active between the 1960s and the late(ish) 1990s. Right now, on blogs and elsewhere, there is a significant amount of debate on Mr P (Prof. P, in fact) so it would be superfluous of me to duplicate that, but I found that, in the last week or so, while reading and pondering and reading some more and writing and rewriting, this post had started to head towards slightly different conclusions from the ones I had anticipated SO, as well as a brief look at his ideas and a medium-length chewing over of their validity, you’ll find my own little conclusions at the end, but I hope they’re of interest. 🙂

Postman’s ideas: an overview

Postman’s main concern was the capacity to interact with information and what he saw as “the conflict between independent thinking and the entrancing power of new technologies” (quote from an obituary by Angela Penny in Flak Magazine). Initially, this meant television, which he felt spoon-fed society – and especially children – information, without them questioning it. Information had become entertainment, in his view, and laterally he also proposed that the information overload on children led to indifference in the face of violence, death etc.

Re. education, he suggested that TV had become the main syllabus provider, rather than school, and he also said that schools were not teaching children to think, merely to act as fact sponges.

By the 90s, Postman’s Huxleyan view of our Brave New World was really taking the ‘worst-possible-scenario’ line. He saw humanity as becoming ‘slaves’ to machines, and thought the world would be full of doers rather than makers, producers rather than creators, information rather than ideas.

Famously, speaking against technology and modern society’s unquestioning acceptance of it, he gave the example of buying a car, saying that when offered electric windows, he would ask the salesman what problem they solved, rather than buying the model with the electric windows ‘just because’. He also pointed at information and technology as culprits behind a modern loss of childhood, as children post-1950 were increasingly exposed to adult information, dressed as adults, played ‘adult’ sports etc, and he claimed that this was the main factor behind a modern child’s ever-lessening respect for his elders, as the boundaries between generations were now unclear.

Of course no thinker or author, however great, only has great ideas. And when ‘influenced’ by a person, we may in fact only be influenced by one idea or one work. Lars von Trier may have been the inspiration Scott Thornbury drew on when choosing the name for his unplugged teaching approach (Dogme) but who would assume by extension that he, ST, also sympathises with a certain moustachioed German dictator? So rather than look at ‘the validity of Postman’, let’s consider his ideas. This is how I see them (though if this is coals to Newcastle, you could skip to Through the stained glass window below):

Hit or miss?

Off the mark:

The main ‘problem’ with Postman’s ideas is history; they remind me of fashions or films, some ageless, timeless, like classier, more elegant items, true masterpieces, and others like – well – New Romantic clothes or Madonna’s films – totally dated. He seemed particularly caught up by that pre-Millennium paranoia which had computers and machines taking over the world. As I read his Technopolis arguments, such as this:

When I hear people talk about the information super highway, it will become possible to shop at home, and bank at home, and get your texts at home, and get your entertainment at home, so I often wonder if this doesn’t signify the end of any community life (from an interview in 1995)

I was reminded of a film I called Denise calls up, about a group of friends whose only contact with each other is via computers and phones. They have reached the point at which they are all afraid of face to face contact, as it is ‘outside their comfort zone’. A father even attends the birth of his child by phone (ie he attends by phone, the baby isn’t born by phone!). It’s quite a bleak film, but does have an optimistic (albeit small) note at the end. When I checked IMDB, I discovered the film came out in 1995, the same year as Postman made the statement above AND coincidentally the same year as the Dogme 95 film movement was born. PURE coincidence? I think not. I also feel that Postman made his predictions assuming that time and progress are linear, but of course they are not, and the birth of interactive internet, also around 1995, knocked progress from that path of doom. The clips Scott recommended were dated 1998. The word ‘blog’ first entered our lives in 1999.

While Postman was ‘wrong’ in this sense, he was just a man of his times. How many folk hit the panic button in 1999? Not a few. As a person who gave birth in December 1999, I still remember being treated as a moron by many members of staff, particularly the US contingent, who were far more tech-savvy than the gently skeptical Brits, for not having stock-piled nappies (or even daipers) for the New Year calamity. Ahem. Yes, well. We made it through, somehow.

Sorry. I’m descending into anecdotes.

Also, it is true that kids aren’t as kid-like now as when we (or at least some of us ;-)) were kids. But it goes way beyond TV and marketing, and to even attempt to analyse that is not what this post is about.

On the mark:

Education is depersonalised in many contexts (always has been), and information and elbows-on-the-table study is prevalent. Transmission rules, ok? In ELT, CLIL is taking the place of imaginative compositions and personalisation (though only where it is NOT used alongside EFL) and children, including my own offspring, can recite monarchs, the parts of a plant and the Periodic table in two or three languages, but have never written a poem or a story. Postman advocated an inquiring mode of education based on the questions students asked and wanted the answers to, rather than the type that answers questions nobody has asked (though this was not exactly a new idea, he may have brought it to new people), and he championed ideas over information. It would be hard to label that as a passing fad. He saw education as a community activity with minimal teacher intrusion, encouraging critical thinking, rather than an individual, isolated activity. His idea was that if you teach a man to work out how to fish and to ask where the fish are, rather than teach him to fish or give him a fish, you’re not just providing him with food for a lifetime, but with a skill that can be applied to other areas. Surely this has relevance in ELT? Learner autonomy. Learner-centred classes. Learner-negotiated syllabus. Support for learners to be able to ask questions right from the start. Dialogue rather than teacher-monologue. A ‘try again’ attitude, rather than a ‘right/wrong’ attitude. Teacher as facilitator rather than transmitter. Peer teaching and a similar line in co-constructed knowledge to Sugata Mitra’s experiment. And to Scott’s Little Idea.

He also favoured interaction with information, in order to help form opinions and reduce the chance of people accepting things at face value. Can we dispute the validity of that argument?

Young Spanish people interacting with information and expressing an opinion, May 2011.

As for Postman’s car/electric windows analogy….well, it depends, doesn’t it. When I bought my car, I was offered air-con. I said no thanks. I lived in the Canaries at the time, where opening the (electric) windows is enough to keep cool. In that context, air-con was surplus to my needs. It was an expensive extra and I was more interested in having a decent radio. (A radio may be an extra in many people’s eyes, but not in mine.) However, my car and I then moved to Seville. Need I continue this paragraph??

It's too darn hot. / Photo by bredgur from Flickr.

Suffice it to say, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with saying no to something you’re being sold if you can’t see a justifiable reason for it – but justifiable reasons will often depend on context and person, so generic statements like You (Do Not) Need Air-Con are totally misleading. This is a way of hooping-looping back to the dogme & technology debate…you can use technology if it’s totally justified as being the best way to do something, if it’s appropriate and desirable in the context (ditto for dogme itself, of course), but otherwise why swallow the sales?

End of part 2.1…

Read on if you dare… 🙂

Through the stained glass window.

Having read a considerable amount on the subject of Postman over the last week or so, I have come to some conclusions of my own, other than those above (Postman knocked twice). This is the more ‘floaty’, philosophical stuff that pops into my head while at the steering-wheel or in the shower. Read on if you dare… 🙂

A stained glass window with its myriad of colours was the image that came to mind, as I chewed over what on earth I thought of Postman…..he seems to provoke such extreme reactions, hero or anathema. And I do like to question and inquire. I’ll admit, he doesn’t inspire me radically in either direction, as his ideas remind me of many others – the questioning mode goes back to the Ancient Greeks – but he did make me think a lot about the following:

Inquiring

Inevitably, I’ve already mentioned some conclusions regarding the type of education Postman was advocating, but just in case, it boils down to the need to be aware and beware of spoon-feeding – and of course this is in total agreement with the conclusions from Sugata Mitra’s experiments, not in conflict with them at all. Both S. Mitra and N. Postman show/argued that the role of the teacher in the transmissive model was inappropriate or even undesirable. While Postman was discussing this in New York, Mitra was proving it in the Indian subcontinent, so it really isn’t a case of ‘oh yes, well, in the West….’. Context is vital in some senses, but people learn basically in the same manner, although their cultural baggage and expectations may be different.

Dogma (as opposed to Dogme), thrive from the passive, spood-fed type of education, so, if we as teachers wish to impose limited vision dogma on our students (or simply an imposed inflexible syllabus), we teach them; if, on the other hand, we would rather they discovered, thought, questioned, processed, created, engaged etc, we should help them learn. The difference is tremendous. As Willy Cardoso (@WillyCard) tweeted the other day ‘All teaching is by definition teacher-centred’ to which my reply was ‘And all learning is by definition learner-centred’. And answering that question they haven’t asked…. that doesn’t sit too well with me. The imposed syllabus in general. I write materials fully expecting teachers to modify them to suit their students, to be selective. But following a syllabus, a syllabus the students have had no say in, with little or no regard for the students as individuals or as a specific group, as some people do? Hmm. Could it be that Postman and Freire shared an opinion here? A similar point of view? So perhaps Postman, Freire and Sugata Mitra come together on this one? No contradictions here. Here we have… coherence. And personally, I not only think we should encourage our students to think, to question and to process while working as a community, but we should help them imagine, dream, express themselves, create and feel confident, hearing an inner voice saying ‘I can do this, I have something to say, I have something to share with this community’.

But that’s just me.

Context

Another thing that came to mind, while reading all this information (henceforth a swearword – I have definitely suffered from information overload while working on this!) on Postman, is the importance of context.

- The context in which those tweets were sent.

- Historical context (pre Millennium bug, pre ‘social’ internet)

- Context defining needs, not generic needs.

Maybe Postman would have been chuffed, but I found myself questioning the critical tweets, those gut reactions, and looking to find what it was that seemed to jar. Of course, it was the fact that the context of the reference to Postman was a talk entitled Six Big Ideas and One Little One. NOT Six Great People and One Little One. So we should have been focussing on the ideas, not whatever it was that Postman himself inspired in us. People are far more complex than their individual ideas, and none of us are mono-dimensional, fortunately. Nietzsche stated something to the effect that truth is the sum of all possible perspectives, which I tend to agree with but Nietzsche also said a lot of other stuff that…. well….

Historical context. We are all the children of our times, and as such, we dogme types need to consider technology as an option, and I think most (all?) of us do, simply because it’s part of where we are in history, it’s ‘here and now. However, we should all – whether dogmer, techy or other – consider the timeless elements too. NOT using technology is far more timeless than using it, as any electronic device will soon be replaced by a newer version. Somehow a flipchart doesn’t date as fast as a laptop; the newer model iDevice will always have more applications or abilities, while dialogue, despite the wealth of possible topics, is always essentially a conversation wherein some speak and some listen (also true of internal dialogue which I feel should also be encouraged, whether inquiring, imagining, rehearsing…). This is 2011: there isn’t a technology-or-not debate, or shouldn’t be one. And just how much technology depends partly on teaching context, partly on the validity of using it. (And what is the validity of using reams of photocopies that will end up in the bin, in our world of concerns for the environment and recycling? For example.)

What year was the photo taken? Five years from now, this will be a photo of antiques... / Photo by Graham Stanley, from #eltpics

Context defining needs. Just as my move from the Canaries to Andalucía affected my need for air conditioning (I still don’t have any, so I’m acutely aware of this need) so our teaching context or rather our learners’ learning context will affect needs. For technology or for anything else – though perhaps not for electric windows. ‘Ah, Postman was a Luddite!’, well, he wasn’t, so the literature says, he was just cautious in his use of Things, not subscribing to them just because they seemed cool. He needed to see a purpose, a justification, and I don’t think this is worthy of criticism. Some folks are just like that, particularly those who don’t buy into consumerism. In a teaching context, of course, we need to consider our learners more than ourselves, but the needs of the class should be the driving force behind what goes on during a lesson, and that will depend on context more than on what the teacher considers cool. ‘Things should solve a problem’ says Postman. ‘Things needn’t solve a problem, they can be for entertainment etc’ say the blogs. Well…. context. If you’re in Palestine or a Brazilian favela, a classroom in Shanghai, or an academy in Zurich your students’ needs are going to be different. Feeling you’re in a safe, stable environment or learning how to do a powerpoint in English? One size does NOT fit all, and you don’t need youtube to make music. Hierarchy of needs, and all that. I’m in Europe. Many of my teens need someone to listen to them, someone to allow them to speak, to ask questions, to believe in them, to motivate them. They rarely NEED technology….. though on occasion, well hey, they do. Context.

Teacher people

And this is the last stop on this long and winding road. The Postman’s route, I suppose. It’s about people. Teachers, in fact, rather than learners. But teachers as people and as … humans.

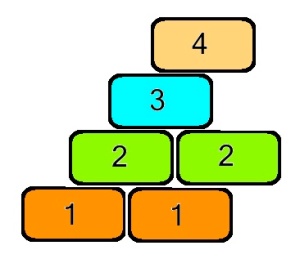

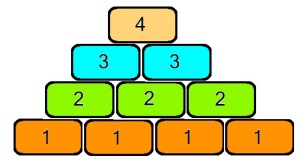

It strikes me there are three basic types, although, as with the terms visual, auditory and kinaesthetic, if you imagine the typical Venn diagram, that would be closer. The three basic types, in my mind’s eye, are the To be, the To do and the To have types. We seem to define ourselves and our values according to these verbs, albeit subconsciously: humanists, existentialist or consumerists/collectors. Prof Postman was presumably not a To have type. I don’t think it’s coincidence that these are the auxiliary verbs in English, or that we have two or three verbs for ‘do’ concepts (make, carry out…) while other languages may have two or more verbs for ‘be‘ or for ‘have‘. The bottom line is, they’re what life is about. Here’s how I look at the types (brush strokes, but you should get the idea), and NOTE, I’m smiling as I write……..

Context is vital – and is he a be, a do or a have person? Hmm. / Photo by Victoria Boobyer from #eltpics

Be folk: ‘I am what I am‘ (or ‘I think therefore I am‘), ‘Less is more‘. These are the ‘who I am as teacher, who my students are as learners and people‘ folk; they’re interested in learner styles, teacher aura, visualisation, sensory stimuli, inner dialogue/voice, mind’s eye/ear …They read and possibly own Stevick, Rinvolucri, Underhill, Arnold, Skehan, Gardner and Teaching Unplugged 😉 Keyword: Who

Do folk: ‘To do is to be‘ ‘So much to do, so little time‘. These are the ‘how to teach, how should I do this activity? And how many different ways can I do this so my learners don’t get bored‘ people. They’re interested in methods, the lexical approach, class dynamics, TPR, grammar games, pairwork v groupwork, adapting lessons for 1-2-1, hands-on learning etc. They read and possibly own Harmer, Lewis, Ellises, Krashen, Ur, Hancock and the Cambridge or OUP teachers handbooks. Keyword: How

Have folk: ‘To have and to hold‘ (or To Have and Have Not). ‘You need one of these‘ These are the ‘what I need in terms of materials to use in order to reach/engage students‘ folk. They’re interested in materials and technology. They read blogs by Peachey, Stanley, Hockly et al and resource books (on a Kindle or similar). They own a wealth of gadgets, applications, flashcards, board games…. Keyword: What ;-D

Obviously, these definitions are slightly tongue-in-cheek (though many a true word …), and we’re all a combination of all three, so, like a combination of the three primary colours, we each have a personal palette, but I’m sure that in life we give priority to one ‘colour’ or another according to our character. Brad Patterson, who has helped me with bits and bobs in this post, says of himself “I’m a do kinda guy 4 sure, but with lots of be activity”. As for me, I’m a be-do-be-do-be-do sort….. so I love music… no, but that explains my whole lifestyle as well as my preferred teaching style and reluctance to adorn my lessons with large amounts of material or technology. I’d far rather be digging and planting in my garden than out shopping, too. Il faut cultiver and all that.

But rather than just considering different learners, auditory, visual and kinaesthetic, maybe we should be more tolerant of different teacher types too, be, do and have, and look at our profession through multi-coloured, stained glass windows – after all, it’s a great, vibrant, living, breathing view.

Photo by creativity and Tim Hamilton on Flickr

Post-data: Two mini challenges for you.

a) Are you a be, a do or a have person? Or a combination of which two, predominantly?

b) Scott named 6 Big Ideas that have influenced him, none of which are from the world of ELT. Can you do the same? How about 3 Big Ideas or Great Names? Who, what and why?

Guido (@europeaantje) is a teacher, but is he a hedonist (be), a swimmer (do) or the owner of the pool (have)? And you? / Photo by @europeaantje from #eltpics

I live in Cáceres in Spain, a beautiful and inspiring sort of place to live, and I’m a teacher, trainer, writer. mother and life-enjoyer. Although I originally trained as a translator and interpreter, I’ve been in ELT since the late 80s and, as a person who trained when Headway was just out, I now tend to teach dogme and am co-moderator of the Dogme web group. I’m big into visualisation, sensory stimuli for the imagination, motivating even the ‘grottiest’ of teens, learner-generated materials and a heap of other things, many of which are not related to teaching, but I give workshops on the ones that are ELT related. I’ve also written coursebooks and other ELT materials.

Many thanks for both guest posts, Fiona! Absolutely loved reading them!! 🙂

It’s also made me revisit some (very??) old posts of mine, in case you’re interested: