I’ve recently attended an event in which there was very brief talk followed by dinner with other educators. In addition to general conversations about the current educational scenario, the main point was to discuss the use of Generative Artificial Intelligence in education. The guest speaker was brief, and he was not there to lecture, but to raise some interesting points as he’s got access to data in both the public and the private sector of primary and secondary education in Brazil. This is not something that we, educators around the globe, haven’t discussed in the past year extensively, and some of the topics that were raised in the follow-up discussion can be easily identified: the need for better teacher education to incorporate new technology, the lack of infra-structure to allow for equitable access in the country, academic dishonesty, and some pointers on how teachers have been using AI effectively in their lessons. All valid points that should be debated more and more often. Yet, there’s one thing that I’ve been doing some thinking about so much that it could be an interesting point to put into writing. It’s been a very long time since I last wrote in this space, and I’m not even sure anyone still follows this blog, but the conversations I was able to have in the comments were always productive and helped me frame my thoughts differently, so here I am again.

The burning question is whether we’re taking the debate where we should take it. We have are witnessing the birth of technology that was able to impress us given how human-like it is. Text generated by ChatGPT back in November 2022 was so impressive because it was easy for us to forget that we were talking to a machine. What was more impressive was the results it got from exams that humans themselves failed. In the beginning the discussions revolved around the death of the English essay, or the fact that now students wouldn’t bother to learn anything – we should, some claimed, ban technology from schools or go back to oral exams and in-class assessments only. To be fair, I guess anything that is so disruptive to well-established practices is prone to causing such fears, and this is not entirely a bad thing. When COVID first appeared, many people (myself included) were overtly cautious until there was a better understanding of how the virus works. When Generative AI made it debut in education, it was still such a new thing with such potential for disruption on well-established practices that such concerns are, in my view, valid to a certain extent.

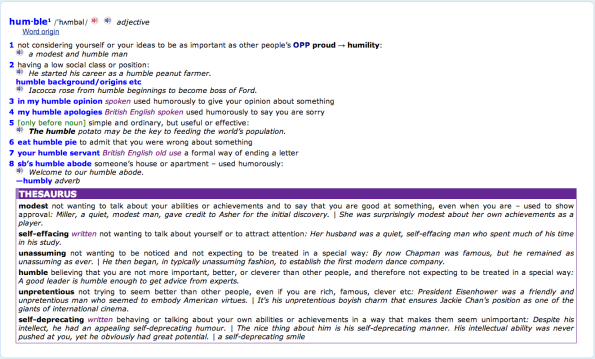

It is a fact that education takes its time to evolve and catch up to new technology. The picture on the left was taken from a report about the prospects of education in 2030 published by UNESCO (I can’t find the link for the life of me!) and it illustrates well what happens when there’s any disruption in the process. I think this happens because in education we’re working with the most precious thing in people’s lives: their children. No one wants to gamble their children’s future into a fad, and we’ve seen quite few of those in the past 20 years or so. Nevertheless, the fact that Generative AI has caused such an uproar not only in the world of education, makes me think that this is might be something more than a fad. Current uses of AI in education, from individualized learning to materials writing, should be taken more seriously as a viable tool that will soon be part of what we do in schools around the world.

My question is whether the focus is right. Yes, AI can help us do a lot of the things we currently do faster, more effectively, and even improve the current practice. However, is this what we should be doing? Any failing system tries to produce more of what it does when it’s failing. AI helps us analyze more and more data generated from standardized tests. It helps us categorize such data and create what we call an individual learning path to learners so they can perform better in those very same standardized exams. Is this what we want? Shouldn’t we go back to the purpose of school and the world that lies ahead given the technological advances, thoroughly revise them, and try our best to modify what we do? Are we simply substituting old practices with new tools, or even augmenting such practices? Is that all?

This might not be a question all over the world, but in a country as large as Brazil, with all the hurdles to reach all students and teachers, poor infra-structure and connectivity, lack of professional development opportunities, the more we try to promote the old system with new practices, I fear we’re simply adding stress to the system. What is it that will allow students to thrive in the world they will face? Do we accomplish that by shoving content down students’ throats in a such a frantic pace? How can we add rigor, or how can we ensure that we are indeed focusing on learning when there’s absolutely no time to do what needs to be done? In the past few years, a lot has been discussed about what we should add to education, conversations about how implementing this or that will benefit teachers and learners. Very few discussions have been had about what we should cross out, scratch, delete from the curriculum. Perhaps the transformation AI is causing in the world will lead us to a more concerted discussion about what to stop doing as it’s meaningless in today’s world. Do we really want to do more of what we have been doing up to now? It’s taken us thus far, but is it what we need to keep advancing? Perhaps this is the moment in which we can benefit about the advances in the science of learning and focus on what’s best for learning. Maybe AI can lead us to focus on the most important thing in the teaching and learning environment: the relationship between the teacher and the learner. If we ask the right questions, new technologies can help us make learning more human again.